Searching for the great Zuby

by E. Micheal Bablin

We swept into the party in a gust of half-melted snow and enthusiasm, the air still thick with the rumors we’d trailed behind us—dumb, persistent, alive. Even before I’d kicked the slush from my boots, a stranger in a frightened yellow sweater leaned across the jammed foyer and informed us, “Zuby just left.” Not “hello,” not “can I take your coat,” but the news, hot and fresh, that we’d missed the sole reason anyone came to these events in the first place. This was the necessary disappointment, the script everyone rehearsed, and as the words landed they left a vacuum in my chest—a hollow, elastic snap like when you pull your hands apart after they’ve been glued with honey.

I stood uncertain in the vestibule, the last notes of someone’s laughter drifting around the corner and up the stairwell, the echo of a joke that had ended just before we arrived. There is a very particular aftertaste to having missed someone: it’s not absence, but presence gone molecular, something spirited into the air and taken up by every nostril. I could feel Zuby’s residue in the heat of the doorknobs, in the way each conversation muted itself as we passed, as if the room itself was a lung that had just exhaled him. Lightbulbs seemed to glow with a more golden, forgiving light in the wake of his departure. Coat sleeves brushed my own as guests shifted and repositioned, seeking a new equilibrium in his absence; I was certain that if I turned fast enough, some afterimage would flicker at the edge of vision, a blur of corduroy or the shaking tail of a sentence unfinished.

My companion (I think her name was Jorie, or possibly Jill; she preferred to be called neither) made a disparaging moue and shrugged her shoulders so far up they nearly met her earlobes. “Classic,” she muttered. “He knows exactly when to leave, doesn’t he?” I nodded, but the truth was less simple. Zuby didn’t just slip away—he became every room’s anticipated absence, the black hole around which every anecdote bent. I could hear him even now, in the story being retold by the credenza, a curling, self-regenerating narrative featuring Zuby as both protagonist and punchline. To miss Zuby was to inhabit a specific loneliness: one tinged with the hope that you might still catch him on the sidewalk, or at the very least, find a memory of him clinging to the banister or the rim of a wine glass.

We spilled further in, past the crowd of grad students and their urgent, peacock displays of cleverness, through steamy archways and into the heart of the kitchen, which was always the heart of any house worth the trouble of visiting. The counters were already stripped of their better offerings; only a single wedge of brie, sweating beneath harsh light, and a heap of bruised apples remained. Someone had lined up shot glasses full of something viscous and green, and a trio of philosophy undergrads hovered, performing the elaborate courtship rituals of their kind—lofty pronouncements, heavy laughter, strategic foot placement. Zuby was a constant reference point: “as Zuby would say,” “like that time with Zuby at the Solstice thing,” “the way Zuby just, you know, is.” It was as if the party had been engineered precisely to amplify his myth, a social echo chamber where his absence was more articulate than any presence.

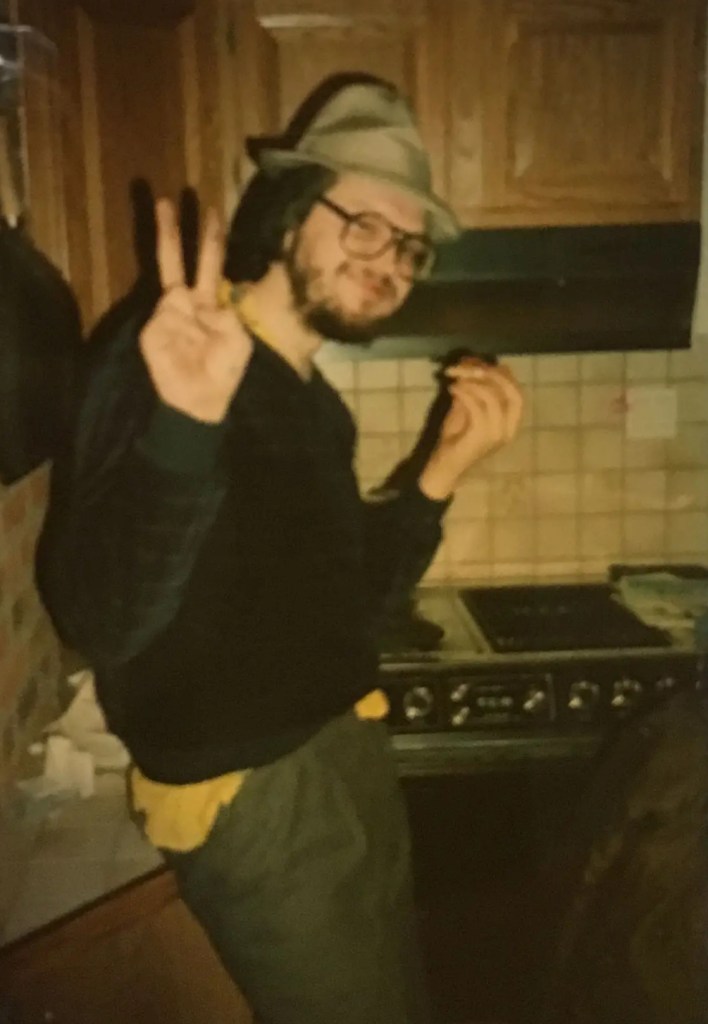

I circled the rooms like a moth, certain that I’d find him if only I looked with sufficient cleverness or persistence. In the den, a woman in a cranberry velvet dress caught my sleeve and asked if I’d seen Zuby’s newest trick—the thing with the carrot and the lighter fluid—because “it’s the only time anyone really believed in magic since third grade.” She let me go only after extracting a promise that I’d report any sightings. On the back porch, a man with the hairless, unblinking look of late-stage academia offered me a cigarette and told me, sotto voce, that Zuby was really just “a symptom of the times,” proof that our generation would never recover from a deficit of authentic charisma. I smoked the cigarette to the filter just to keep him from asking my opinion.

Above all, I was haunted by the certainty that Zuby was not truly gone, only lurking in a probability cloud, waiting for me to look away so he could collapse back into certainty. I remembered every previous encounter: the time I lost him at the mall, only to discover him in a mall I’d never heard of, three hours away; the time he left a wedding in the middle of a slow dance, only to appear in the wedding photos, arm-in-arm with the bride’s great aunt; the time he showed up at my own birthday party, uninvited, and vanished again before the cake was even cut, leaving behind a signed playing card and a single, perfect origami swan. Zuby was always two steps ahead, which meant I could never catch him, but I could try, and for reasons I could never articulate, I always did.

I kept moving, because motion was the only way to stay in the gravitational field Zuby left behind. As I pushed through the crush in the living room, a volley of laughter shattered the conversation and everyone’s head swiveled toward the staircase. For a nanosecond, I felt a seismic shift—was it possible, had he returned? But no, it was only the host, flushed and panting, holding a tray of mismatched shot glasses and telling everyone that the real party would be on the roof. My disappointment was so palpable that Jorie/Jill called me out on it in front of half a dozen people.

“You know he’s not actually better than anyone else,” she said, and the words rang out with that peculiar clarity that only comes from mild intoxication and private disappointment. I didn’t answer, because the question wasn’t whether Zuby was better; it was whether I would ever be satisfied with merely being present when Zuby was not. I drifted through the rooms, gathering stories and fragments, cramming them into my pockets like so many party favors: the legend of the time Zuby ate an entire lemon, rind and all; the rumor that he once convinced a dean to cancel finals for an entire department; the whispered assertion that he’d been seen, recently, at the train station with a suitcase full of unmarked envelopes, headed somewhere no one could pronounce. I collected them all, not only for myself, but for the future moment when I’d encounter Zuby again, and he would expect me to be up to speed.

The night, as all such gatherings are fated to do, began dismantling itself with a sort of cunning inertia—a slow-motion collapse masked by the crescendo of stereo, the clatter of empties, and the mounting warmth of bodies. There’s always a moment, never marked but always known, when the party’s spirit snaps from exquisitely possible to irretrievably gone, and I could feel it happening even as I made my slow, thwarted orbits of the house. The kitchen, once a warren of tactical flirtation and wine-glass semaphore, had thinned to a few diehards pecking at the remains of the cheese plate, scraping the wax rind for dregs of flavor. The living room, which had seemed so vast and luminous when I first entered, now bristled with conversational knots—tight, insular clusters of laughter that closed ranks whenever I approached. Even the staircase, which had earlier functioned as a kind of social launchpad, now bore a single, desultory couple huddled together and discussing, in voices barely audible, whether to call a cab or push their luck for another hour.

I moved through these spaces with a sense of mounting unreality, half in the moment and half remote, as if watching my own life from a mezzanine. With every lap around the house, my certainty that Zuby might still be lurking somewhere—some hidden pantry, some shadowy guest bathroom—grew at once more desperate and more absurd. I began to notice the other repeaters, the pilgrims on their own private circuits: the guy in the baseball tee who compulsively checked his phone in each room, the woman who kept losing and then finding her purse, the philosophy undergrads orbiting the liquor table in search of a new audience for the same, slowly mutating anecdotes. In their movements I saw a kind of kinship, a silent acknowledgment that we were all here not for the party itself, but for the possibility that something—or someone—might yet happen.

As the hour grew later, the boundaries between rooms and between strangers eroded, and the house became a single, undulating organism—louder, sweatier, more prone to spontaneous eruptions of song or dance or sudden, inexplicable weeping. I found myself wedged into a hallway alcove with three acquaintances whose names I could not retrieve, all of us shouting to be heard over a Stevie Nicks song that had been put on ironic repeat. One of them, a guy with a beard sculpted so precisely it felt like a dare, confessed to having once taken a road trip with Zuby and “some girl who only ate beige foods.” This led to a round-robin of Zuby stories, each one more improbable than the last: the time he’d convinced an entire pub to sing “Happy Birthday” to a goldfish; the night he’d gotten locked in a botanical garden and spent the entire evening naming every plant after an NBA player; the semester he’d infiltrated a sorority under an assumed name, lasting nearly two months before exposure. For a while I was content to listen, letting each new tale layer itself onto my own mental collage of the man, but eventually I found myself staring at the baseboard, counting the carpet tacks, my attention fraying at the edges.

I slipped away, quietly, and drifted toward the back of the house, following the faint pull of cool air and the promise of temporary solitude. The sliding glass door led onto a narrow deck, where a handful of smokers shivered in their coats and watched the streetlights halo the falling snow. Here, conversation took on a different timbre—softer, less performative—and I found myself unexpectedly confiding in a woman with a cigarette perched at a comical angle from her lips. She asked if I was “one of Zuby’s people,” and I hesitated before answering, unsure if the category was meant as praise or mockery. When I finally nodded, she offered a knowing, almost sympathetic smile, as if to say: You’re not the first, and you won’t be the last.

We talked for a while about nothing—weather, the relative merits of local pizza places, the enduring mystery of who actually owned the house—before the conversation drifted back, inevitably, to him. She told me that Zuby had called her once in the middle of the night, from a payphone at the edge of a county fair, just to read her the entire text of a warning label he’d found on a ride called the Zipper. “He said it would be important for me to remember it one day,” she laughed, taking a drag. “I still have no idea why.” There was no bitterness in her tone, only a kind of bemusement, as if she’d long ago come to terms with the fact that Zuby’s logic was a closed system, self-consistent and utterly impervious to outside influence.

I left the deck and wandered back inside, where the party had reached its final, inevitable stage: the scattered survivors, the makeshift beds assembled from couch cushions and throw blankets, the host moving from room to room with the dazed affect of a parent accounting for children after a storm. There was a sense of aftermath, of stories already congealing into legend, and I felt a loneliness so acute it bordered on the sublime. I circled the house one last time, testing every door, peering into closets and behind curtains, half-hoping for an apparition, a last-minute reversal, a Zuby-shaped shadow thrown against the wall by the glow of the refrigerator.

Instead I found myself alone in the mudroom, staring at the heap of winter boots and coats that had multiplied during the course of the evening. I sat on the bench and listened to the muffled echoes of laughter from the other rooms, their voices at once so close and so impossibly distant. It struck me then that Zuby’s absence was not a single event, but a condition of the world—a kind of weather, always moving ahead of you, always receding even as you pursued it. I felt the urge to call him, to leave a voicemail or a text, but I knew better. The game was not to reach him, but to keep reaching, to stay in motion even as the coordinates shifted and the target dissolved.

Sometime after two, I found Jorie/Jill slumped in the armchair, her posture gone loose and provisional. She roused herself enough to smirk at me and say, “You’re still looking for him, aren’t you?” I didn’t deny it. Instead, I asked her if she thought anyone would really remember this night, or if it would just blur into the general wash of parties and semesters and years. She thought about it, then said, “Every story needs a Zuby, even if he’s not around to hear it.” I liked the sound of that, even if I wasn’t sure I believed it.

As the party dwindled and the house emptied, I began to help with the cleanup—tossing bottles, stacking plates, wiping the sticky residue from the counters. It was a small act of faith, a way of insisting that the night had mattered, that the evidence of our presence should linger at least until morning. For a while I worked in silence, then with the host, who was grateful but too tired to say much beyond thank you and good night.

Eventually, with the house returned to a semblance of order, I stepped outside into the cold, the snow now falling in thick, leisurely flakes. The street was empty, the windows of the neighboring houses dark. I stood for a long time on the porch, letting the night air bleach the noise from my head, and thought about all the places Zuby could be—some after-party, some diner, some train already out of town. Or maybe, just maybe, he was nowhere at all, content to exist in the stories we told about him.

But I kept moving, scanning every face, every doorway, every possibility, waiting for the moment when the great Zuby would materialize again—if not in this lifetime, then in whatever lifetime awaited the people who never learned to stop hoping.

Discover more from Site Title

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.