Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Iran has fallen the god/king is dead, that is what an Ayatollah is after all. For the common man—whose agency matters only as a shadow upon the palace gates—the very notion of selecting, by human hand, a god/king is heresy raised to the level of farce. This is not a realm of “voting,” nor one of inheritance, nor even of silent, ancient ritual: Perhaps, if one believed the old stories, the god/king had always existed, only putting on new flesh when the old was spent. In the Ayatollah’s Persia, not even the intricate machinery of the Assembly of Experts nor the bureaucratic hydra of the Islamic Republic could obscure the core: a god/king was ordained, not selected. And yet, history’s gutter is filled with the bones of ordains and the wails of the ordained.

But what, then, when the mechanism falters, showing a trait not predicted? If the god/king, standing secure in the design of authority, is cut down—not by the slow consumption of age, but is killed by the so-called Infidel whom he claims is harmless against the shield of god? The established stories make little allowance for this. The Prophet’s time offers no tale to suit; Byzantine chroniclers, too, record no instance of it; even the Gnostic desert mystics, whose whispered heresies drift far from convention, say nothing of an outside hand breaching that sanctified circle and laying the god/king low. If such a thing were to occur, one might well see it as the old court poet described—a rip in the tent, sudden and wide, exposing the night sky entire.

Excerpt from new dystopian novel “The Graces of Bliss Hall “

By E. Micheal Bablin

She remembered, with a kind of lucid, silent ache, what it meant to be at Bliss Hall—the first and only time in her life that rules had shaped her as much as love. The rules were strict, almost monastic in their precision, and the older Graces enforced them with the same blend of ferocity and tenderness that the matron herself possessed. The matron, even now, was a shadow in Grace’s mind: upright in her woolen skirts, eyes quick as buttons, voice never raised but always absolute. Don’t leave the dormitories without your apron. Don’t speak unless addressed. Don’t let your hair fall loose, don’t let your slippers scuff the corridor tile, don’t, don’t, don’t. The phrase “a Grace must always follow her keeper” had been printed in curlicued letters over every mirror and embroidered in blue silk on the dining hall banners. In the beginning, Grace had thought of the rules as a maze; later, she saw the walls were not meant to confine, but to guide, and she’d begun tracing their logic not with resignation, but relief.

It was the older Graces who instructed the new girls in the art of yielding. They would gather the youngest at dusk, herded in the tiled vestibule outside the chapel, and teach them to smile, to bow, to speak in the quiet, careful way that left room for another’s thought. Some of the girls bristled at first, and some had to be taught twice, or three times. A few, like Grace, learned instantly. She never asked why; she simply understood that to surrender was to belong, to submit was to be noticed, and to be noticed was to be loved, even if the love came as a stern glance or a corrective hand on the shoulder. As months passed, the rules became less like instructions and more like the quiet interior skeleton of her body, holding her upright and directing her movements as surely as any muscle or nerve.

She remembered the Fall semester, when Simon was selected to be her Keeper. The staff smiled with a particular pride that Grace only understood much later; to be chosen as a Grace was an honor, but to have a keeper like Simon was something else entirely. The first time she saw him, he was standing stiff and uncertain in the parlor, his broad hands knotting and unknotting themselves behind his back. He was only eighteen but had a gentle smile and everyone could tell he really cared. Grace had been summoned to the parlor for a brief introduction, but the air between them was so charged that even the matron’s voice seemed to slip away, leaving only the thrum of Grace’s own pulse.

With Simon, everything became a kind of grace. The night he undressed her, it was not boldness or demand but a certain carefulness—a gesture remade. Water ran over them as he guided her gently through the shower, his hands saying what words could not. Then he wrapped her in a towel, brushed the hair from her face, and settled her into the bed as though it were a quiet promise. He curled around her, his arms folding her into a hush. She felt herself yield to it, to him, and inside the surrender was something astonishing: she let him take control, and she loved it—not as captivity, but as belonging.

The rules were simpler, but the feelings behind them were not. Obedience was no longer just a performance; it became a way to forge a tunnel, straight and glowing, between her heart and his. When he visited, he would walk with her through the frost-bright orchard, and she would watch the way his boots sank and then rose from the snow, each step leaving a perfect cavity, as if the earth itself had been waiting for his weight. Sometimes he would take her gloved hand, and they would walk together, silent and sure. Once, in a moment that felt like the shocking flare of a match in a cold room, he pressed his lips to her cheek, just below the eye, and she realized—for the first time, truly—that he loved her not for her obedience, but for the way she wanted to obey.

After that, the rules at Bliss Hall became less like a puzzle and more like a promise. Every lesson, every restriction, every small triumph of self-control had been for this: the slow, deliberate matching of two people who might otherwise drift, soft as dust, never finding a shore. No one ever said this out loud, not even the matron, but Grace began to see it everywhere: in the way the dining room candles were arranged in pairs, in the patient hand of the gardener as he tied up the clematis, in the hush that fell between Graces and keepers when they passed each other in the corridor.

By the time she left Bliss Hall, Grace had come to crave the boundaries it had imposed. She realized this in the first days at Simon’s house, when she rose before dawn to sweep the hearth and lay the table, even though no one expected it of her. She realized it again when Simon, gentle but insistent, corrected the way she folded his shirts or stirred his tea. These small corrections made her feel visible, real, woven tightly into the fabric of the house and the day.

In the new house, Simon moved with a certainty that awed her. He was not loud or boastful; he inhabited the rooms the way roots inhabit soil, invisible but essential, holding everything together beneath the surface. Grace watched him as he made the rounds each evening, clicking off the lamps in the parlor and kitchen with a kind of ritual solemnity. Sometimes he would pause behind her in the hallway, one hand resting light on her shoulder, and she would look up to see him smiling—not indulgently, but with a clear, steady affection that left no room for doubt. The world had narrowed to the shape of his gaze, and in that focus she found a peace that was almost narcotic. The endless, nervous calculations of her old life—the fear of misstep, the constant scanning for cues—fell away. There was only Simon, and the strong, silent system of his approval and correction.

She learned to read him as she once read the matron, but with a difference: where the matron’s rules had been iron bars, Simon’s expectations were more like the lines of a sonnet, giving shape and music to her days. If she forgot to leave his coffee by the window, he would say nothing, but she would notice the flicker of disappointment, quick as a moth’s wing, and correct herself the next morning. If she spoke out of turn in front of guests, he would gently squeeze her hand under the table, a warning and a comfort all at once. These small, wordless lessons became the current of her life. She began to anticipate his needs, to move through the house as if tracing a secret map known only to the two of them. Each time she pleased him—a well-made bed, a perfect roast, a moment of quiet deference—she felt a glow inside her ribcage, a sweetness so rich it sometimes caught in her throat.

She was not foolish; she knew some would call it submission, or worse. But Grace understood that power passed between people in more ways than mere command, and that the deepest kind of belonging required both boundaries and a mutual yielding. Simon gave her a structure as intimate as a skeleton, and in return she gave him the soft, vital tissue of her attention, her effort, her care. When she succeeded, the approval in his eyes was not just for her service, but for the fact that she had understood him, had met him fully in the world he wished to build. She had never known love could feel like this: not a fever, not a hunger, but a kind of shelter, a wall against the jagged cold of uncertainty.

Sometimes, in the evenings, she would watch the shadows lengthen across the living room carpet and think how strange it was that she had ever needed the vigilance of the matron or the chorus of her fellow Graces. Now she needed only the structure of Simon’s days and the assurance of his presence. The memory of Bliss Hall faded, not into nothing, but into a kind of softened echo, a set of lessons transformed by the new context of their life together. Her former longing to be singled out, to be chosen, had become the quiet constancy of being seen and valued, every day, in small but perfect increments.

And when she lay awake beside him at night, his breathing deep and even, she would sometimes try to remember the girl she had been before all this began—before the endless rules, before the compact certainty of Simon’s regard. She reached for that girl in her memory, groping for the clever, brittle self that had arrived at Bliss Hall with a battered suitcase and the crust of a strange aunt’s affection. That girl had trembled at the prospect of being called out in chapel, of having her faults displayed. Now, the idea of correction—of being seen, measured, and guided—felt less like a threat and more like a gift, something spare and glowing and infinitely precious.

Her memories were a chain, each link bright and distinct: the first time Simon touched her neck, the time he carried her across a rain-slicked path instead of letting her shoes get muddy, the afternoons they spent reading together in the parlor, his voice low and deliberate. There were darker memories, too—the stiffness of the matron’s hand, the cold fury of a punishment administered in the silent corridor—but even these had lost their sting, turned to something instructive and almost necessary. Everything led to now, to this moment: Grace, in the kitchen, her hands sunk deep in bread dough, the scent of yeast thick around her, Simon’s footfall steady on the stairs.

It was in this moment, more than any other, that she understood the secret lesson of Bliss Hall: that all the rituals and boundaries were not about subjugation, but about safety, about creating a world where it was possible—at last, and entirely—to belong. The girls who became Graces, the boys learning to be men; each finding their place by loving and being loved, by linking their lives as neat and sure as the latticework on a garden wall. To belong, to be brought inside someone else’s logic, securely enclosed where nothing could startle you loose or leave you floating untethered.

That memory lived inside her, glinting sharp and bright—a thread running through everything she did: the first shy shock of Simon’s fingers, the way it thrilled her to discover how Simon watched over her, kept her close, made her his own. The sensation was more than simple happiness; it filled her head and bones with something complete and certain—a gentle, flawless relief, knowing she belonged. Kissing her Simon was only about sweetness; it was a yielding, a deep letting-go, trusting that he would keep her safe, invisible connections drawing her to him, so steady and sure she never had to question her place.

To love Simon was to find her rightful shape: boundaries clear, edges marked and known. There was comfort in it, a deep peace in never having to wander lost, never dissolving or trembling on the verge of vanishing, never facing the dark echo of solitude. Safety shone in obedience, in the knowledge that her place was hers alone; she could rest in that enclosure, never lost, always, always held.

Now Grace was pregnant with the product of Simon’s love, and it was written everywhere on her: in her shy, delighted smile, in the way she held herself a little differently, as if something delicate and astonishing had taken root inside her. She almost couldn’t believe it herself. The thought sat new and ridiculously sweet in her mind, like the secret candy she used to steal from the pantry as a girl, something secretly hers, a tiny sweetness she could let dissolve on her tongue, day after day.

Simon stayed close. He knew what the weeks meant, knew how every flicker of her body mattered now, and so he watched her with careful, constant eyes, ready to catch the smallest change. Maybe that’s what being in love was: living inside someone else’s heartbeat, afraid that if you missed a single signal, you’d lose the whole world. The days stretched out around her, slow and golden, every one thick with impossible, ridiculous hope: would the child be a boy, or a girl; would their hands be delicate or strong; who would they love, who would teach them how? Questions multiplied, filling whole rooms, making the house seem larger, softer, as if the simple air had turned to possibility. Always Simon, always his hands, steadying her through each day.

Grace could feel it—the new tilt to the future, the way everything seemed to glow and blur outward from this small, secret kernel of hope. She was the good earth now, full of what Simon had planted, and all either of them could do was wait to see what would take shape, who would come next, and how love would grow.

With Grace’s due date drawing near, she leaned in to his care—not a lapse or an experiment, but a sequence of gestures rehearsed with such precision they became their own sort of ceremony. Her hands, constant now, would smooth the counter, refold his shirts, tip the pills into his palm as if each movement might be inspected for faults neither of them had yet named. There was a rhythm to it, something that felt at once unfamiliar and inevitable, as if the arrival of this first child had started a quiet reordering. Their household, once a loose collection of habits, was beginning to knit itself around the child to come, and all the unseen others that suddenly, impossibly, seemed almost certain to follow.

E. Michael Bablin

We’re halfway home and I can’t stop watching the rainbow in the rearview. It’s all I want to look at, even though I’m the one driving and Bro is in the passenger seat scrolling through his phone, reading out loud some TikTok drama and then lapsing into silence so the car fills up with more of the soft jazz that he never admits he likes. But the rainbow—hell, it’s a monster, a cartoon of itself, it’s this mucilaginous, absolute band of color, the kind that only happens in bad tattoos or the covers of physics textbooks. There’s still a little rain spitting so the road is wet, glistening with an oil slick shimmer, and the rainbow is reflected everywhere—on windshields, on the lake glass, even in the droplets that hang on the edges of the wiper blades. It’s a whole dome, a bubble big enough to hold the entire town, and all the colors are so stupidly bright and distinct that there’s no point trying to name them. It’s the rainbow and I know it’s for me, like the way a good omen can follow you home, and I keep thinking about how it will look from our driveway, whether it’ll hang over the roof or dissolve before we pull in.

We pass the overpass, concrete still dark with rain, and the rainbow dips down low, cutting through the haze that’s left once the sky clears. For a second the rainbow gets wrung out and pale, then it comes back even harder, like it’s been plugged in and someone cranked the saturation. I flick the wipers again and Bro glances up, sees where I’m looking, and says, “Bro, that’s the gayest rainbow I’ve ever seen,” which is the sort of thing he says when he means it’s beautiful and he wants it too but pretending not to care is his whole deal. I don’t answer, just squint through the windshield and try to memorize the curve of the arc. It’s all I need—this sense that the rainbow exists even when I’m not looking, that it waits for me, sits there like a badge or a signpost or the simplest promise that something can be absolutely true in the world.

The rain lets up almost instantly, just a few spatters along the edge of the glass, and where the rain ends is exactly where the rainbow begins. It’s so sharp it feels like you could drive right up to the edge of it, or maybe like you’re already inside of it, the whole car sealed in by color. I think about contentment and what it means to have something solid that you always come back to, even if it’s just a trick of the light. There’s still so much left to do—school, work, writing, the entire huge haul of days ahead—and I think about how the rainbow will outlast all of it, how it will keep showing up in the same place every time there’s rain and sun at once. I wonder if I’ll ever get tired of it, if at some point I’ll just stop looking up.

But right now the rainbow is the whole show and the street is empty, and we’re close to home and I slow down so I won’t lose the view. I’m already planning how I’ll describe it, which words to use, but none of them will be enough because the rainbow is exactly itself and nothing else, not a metaphor, not a hope, just the world doing its thing and me getting to see it. Even after we’re inside, I know I’ll keep thinking about it, about how it follows me, about how it waits for me each day I come home.

am, right in it, the rainbow as the view It becomes a thing I chase, not just in the childish sense, but as a real orientation, a gravitational slant to my entire day. I’m up before the streetlights blink off, before the heat kicks in, and it’s there—if not in the raw sky, then in some residue on the apartment walls, a prismatic shadow crawling over the eggshell paint as the sun comes up behind the mist. It doesn’t matter that it’s October, that the forecast says only drizzle and fog, because this rainbow is stubborn, engineered out of the angle of my window and the steady damp in the air. Sometimes it’s so faint I have to squint for it, other times it’s enough to make the whole living room look staged, like I’m living in an ad for vitamins or fast internet. The rainbow: always there, always performing, even when there’s no one to watch but me.

October, and it inserts itself into breakfast: in the sweat-condensed beadwork on my mug, the slow drip down the inside of the French press, the way it bands itself—clean and miniature—across the surface tension of the spoon. It overlays everything, not just color but clarity. Rainbows on rainbows, and once, when the clouds finally break for an hour, there’s a double, two identical arcs, perfect as parentheses, framing the bare trees and the crows shouting over the power lines. I can’t help but see it as a bracket around my entire life, a pair of arms drawing a territory just for me. I lean against the counter and stare until my eyes water, thinking: here I am, exactly where I’m supposed to be, mapped by these bands of light.

It’s not that the rainbow is special, I remind myself. This street is like any other, a lazy curb, cracked sidewalk, the early walkers out with their flannel and their dogs. But the rainbow gives it context, and more than that, it feels like it’s making a point out of simple repetition. Every day, in some form, for weeks now—refined and present, a challenge and a comfort at once. It’s not a reward; it’s a constant. I don’t need a diploma or a letter of acceptance. I just need to stand still and let the thing find me. I wish I could tell Bro, or Mom, or someone, but I know it’s better as a secret, something too huge and dumb to explain in a text.

I try to write about it. I open the Notes app and type three lines, delete them, start again. There’s no way to get it across—the way the rainbow shifts from a visual to a presence, something that hovers and presses, that tints every other thought I have. I remember reading about how a rainbow isn’t real, how it’s just a direction, a condition of the eye and the rain and the angle of the sun. It only exists because you look for it, and if you move, it moves; if you blink, it’s gone. I write that down and let it sit, watching the light crawl up my hand, the way the veins and tendons get painted in impossible color, like I’m being made and unmade in the same moment.

I’m not in love with the rainbow—don’t get me wrong. It’s not a metaphor for anything, not some sign from the universe. But it’s there when I wake up, it’s there when I pedal the bike to campus, it’s there in the puddles and oil slicks, in the smeared rear window of the bus, in the condensation on every bathroom mirror. It’s an epidemic, a viral persistence, and I think maybe that’s what I need right now: not a goal, but a structure, something visible and predictable when everything else is so shifty and made of air.

The dome of it is what I keep coming back to. Not just a stripe, but a whole hemisphere, a planetarium shell projected over the world. I imagine what it would be like if you could walk along the inside of the arc, hands pressed to the wet glass, feeling the spectrum wash you clean every way you turn. I think about explaining it to Dr. R from physics last semester, how he would go off about optical density and refraction, about how the rainbow is never in the same place twice, how everyone gets their own private version. That feels good, somehow—like this is not just my rainbow, but one that’s built for every person dumb enough to get up early and look for it.

Some days it’s so bright I start to laugh, like it’s trying to get a rise out of me. Once, the rainbow gets into the living room before I do, and I catch sight of it on my way down the hall: a full color wheel turning across the flat of the floor, leaking through the cheap blinds in a patchwork that lights up the dust in the air. I step into it and stand there, waiting for something to happen. The air smells like wet brick and burnt toast, and for a second the only thing moving is the rainbow, crawling across the room as the sun shifts behind the clouds. I could stand in this light forever, but Bro yells from his room to tell me I’m going to be late, and the spell breaks. I shuffle out, but the rainbow comes with me, splintering off the hallway mirror, curling around the banister, fractaling into the day.

I’m obsessed enough to track it, checking the hourly weather, plotting the angles, noting little differences—today the blue is wider, yesterday the red was bleeding into the orange. I start to take pictures, but the phone camera never gets it right, always flattening the color, making it look like a sticker slapped on the sky. I have to give up on the idea of sharing it, because even when Bro looks up from his phone and squints out the window, he just shrugs and says, “That’s cool, I guess.” No one else seems to care, and that makes it better. I let the rainbow have its little life as my own.

But sometimes, late at night, I replay the day and wonder what happens if the rainbow stops showing up. If a week passes with nothing but flat gray and the windows stay dry, will I be able to stand the absence? Will I default back to the person I was before, filling every blank moment with noise or food or the next half-baked project? I try to picture the room without the bands of color, the streets without the oil slick shimmer, and it feels small, a little suffocating. I decide not to think about it. I tell myself there will always be rain and always be sun, and as long as I wake up early and keep an eye out, there’s a chance the rainbow will be waiting.

I remember a time when I was little, maybe six or seven, and Mom took me to the science museum. There was a glass tunnel, and if you walked through at the right time of day, they’d filled it with artificial mist and project a fake rainbow along the curve. Every kid would run through, trying to catch the end of it, but the rainbow always stayed a step ahead, always out of reach. The guide told us it was impossible to touch, that you could never stand at the end of a rainbow, because you carried it with you everywhere you went. I didn’t buy it then, but now it makes sense. The rainbow is a chase, a moving target, but it’s also the reward: you just have to keep walking, keep looking up, and it’ll come find you.

I think about the double rainbow, how it marks out a kind of border, and I wonder if there’s a word for that feeling: not arrival, not belonging, but a sense of having been selected by the universe to witness something stupid and beautiful, even if it doesn’t last more than a few seconds. The rainbow doesn’t care if anyone is watching, but it still makes a show of it, strutting across the sky like a dare. I want to learn how to do that, how to exist just for myself, bright and untouchable and absolutely present.

I make it a ritual. Every morning, I look for the rainbow first thing, before I brush my teeth or check my phone, before I do anything else that matters or doesn’t. Sometimes it’s there, sometimes not. On the days it’s missing, I notice the lack, but I don’t panic. I know it’ll come back, because rain is always in the forecast, and autumn is just getting started. The rainbow is my check-in, my confirmation that the world still works, that the rules of light and water haven’t changed overnight. Most days, that’s enough.

I can feel the rainbow even when I don’t see it—the way it lines up my thoughts, gives order to the mess of my head. I try to think of other things, classes or Bro’s drama or what I’m going to do after graduation, but the rainbow always elbows back in, demanding its due. It’s become a part of the architecture, a fixture like the squeaky door or the noisy fridge, but so much more precise. The rainbow is always in the same place, at the same time, but never exactly identical. There’s a lesson in that, maybe, but I’m not ready to spell it out.

I tell myself it’s only a trick of the light, but it feels like more. A presence. A guarantee that when I look up, something will answer back. I like how that sounds, even if it’s just a lie I repeat until it’s true. I wonder if other people

every time I move, always there whether I’m brushing my teeth or microwaving leftovers or just standing there, looking, not even pretending to do anything else. In the kitchen, the rainbow runs a stripe along the wall above the toaster, bends itself to fit the corner of the cabinet, flickers off the dull white of the fridge. At breakfast I watch it halo the rim of my coffee mug, see it flicker in the spoon before I stir in the sugar. There’s something about the way it multiplies—first one, then a double, sometimes more if the angle’s right—and suddenly it’s rainbows all the way down, each one stacked on top of the last, never quite in the same place as before, but always nested together, repeating the arc and the color and the idea of it until you can’t find the edge of where it starts.

Sometimes I feel like the rainbow is a message, not from God or the universe or even the weather, but from the day itself, like every morning it’s trying to tell me what the day is going to be, or at least what it already is. Sometimes it means I should try harder, sometimes it means I should let myself go, sometimes it means I should keep my mouth shut and just be glad the rainbow is still here. It follows me back to my room, the colors stretched out and warped across all the posters and the cracked ceiling, a prism that never lines up with itself but never goes away, either. I think about that: how some people grow up with banners or medals or team colors, but for me the only flag I ever saw hanging in my room was the rainbow that showed up in October and sometimes lasted till December if the weather was right. It’s always there with me, not as a label or an answer or even a comfort, really, but as a dare. Like, can you be as obvious as this? Can you be as complete and ridiculous and unmissable as this? Can you be as honest as a rainbow, which is to say, can you be a thing that only exists because of every other thing happening just the way it does, can you be content with being the result of someone else’s light passing through you?

Even when I try to leave it behind, the rainbow comes with me, stuck in the oil slick on the sidewalk, in the glare off parked cars, in the flash of CDs stacked in the thrift store window. It’s inescapable, not just for me but for everyone who happens to look up at the right minute. I try to take pictures but they never work—the rainbow is always too bright or too washed out, too much for the phone to handle, too much for me to catch in a way that doesn’t flatten it out or turn it into something it isn’t. So I keep it for myself: the rainbow as memory, the rainbow as anchor, the rainbow as the reason I get up in the morning and the reason I can still come home after a day of being something less than the whole spectrum I’m supposed to be. I keep waiting for it to go away, for the sky to forget how to make it, but every time the rain lifts and the sun comes back, there it is, a little more faded or a little more intense, but always there, a signpost or a checkpoint or even just a joke the universe keeps playing on me, day after day, year after year.

I can’t decide if the rainbow is something I’m supposed to live up to or something I’m supposed to just live with. Maybe both? Either way, it’s always here; it isn’t something I graduated into or earned with a diploma or a clever essay, it’s just a fact, a condition, a challenge that can’t be shirked or failed or passed off on someone else. It marks out the space where I’m allowed to exist, the patch of the world that no one else can take from me, the bubble that holds all of my best and worst selves and tells me, here, this is yours, you don’t have to be anything else. The rainbow is not only for me, but it is of me, and that’s what matters: Rainbow is me.

Walking on the sidewalk beautiful fall day no clouds orange trees red trees leaves are falling happy and sad at the same time next year‘s smells of apple pie and baseball coming home for McLeron school to watch the World Series I am i 60 years old in 2022, or I’m I 10 years old 1972 I can’t seem to figure it out

The sidewalk was a strip of gray static running through the riot of the neighborhood’s color, and I followed it like a pulse line, trying not to step on any of the cracks because I still half believed the old rhyme about broken backs. The sun was out, warming my ears and the bridge of my nose, but the air was sharp—one of those perfect fall days, no clouds, just a blue so clear it felt like a dare. My feet shuffled through the ankle-high drift of leaves that had piled up along the curb, and each step set off a new crackle, sharp and brittle and loud, the sound of endings and beginnings all at once. I couldn’t decide if the trees were orange or red or just on fire, so I settled for all of the above, letting the colors burn through my eyes until I could smell them, the singe of crushed maple and the near-rotten sweetness rising from the grass where the leaves got wet and clumped together.

There was a weird ache in my chest, the kind you get when you realize you’re exactly where you want to be and also afraid you’ll never be able to stay there. The world felt smaller in the fall, like the sky and the ground were squeezing together to keep me in place, but it also felt infinite, because with every breath something new was happening—a gust of wind, a squirrel breaking cover, a neighbor shouting down the block, the sure rhythm of the day rolling on whether or not I wanted to move with it. Every sense was full. The taste of cold in my mouth, the echo of distant laughter, the sugar-and-cinnamon smell of pie from someone’s open window. I could almost see the years stacking up around me, layer after layer, the memory of every other walk home crowding into this one moment until I wasn’t sure if I was ten or sixty or both, stuck in a loop where nothing changed and everything did.

Ahead, the sidewalk turned and the air changed with it, the wind carrying the faraway scent of something scorched—maybe a backyard fire pit, maybe someone burning dinner—and underneath that, a dark, earthy note that was pure October. The leaves made a new pattern on the ground with every hour, and I watched the shadows flicker over my shoes, watched my own shadow shrink and stretch with every step, never quite matching the way I thought I looked. My backpack felt heavier than usual, even though I’d forgotten most of my books at school, and my hands kept drifting to the zipper to make sure it was still closed, that nothing important was falling out as I went. That was the other thing about fall: it was always a season of almost-lost things, of remembering too late or just in time, of holding on a little tighter because you could feel the days getting shorter, the sun setting a few minutes earlier every afternoon.

I didn’t know what I was supposed to feel—proud, like I’d made it to the next grade; nervous, because I was already behind in two classes; sad, because the year was almost over and I hadn’t done any of the things I’d promised myself I would; or happy, because this was my favorite time of year and the entire block seemed to know it, seemed to dress itself up just for my benefit. Mostly I felt tangled, like the present and the past were walking side by side, each one daring the other to sprint ahead and leave me in the dust. Somewhere between the sound of the leaves and the distant crack of a bat on a baseball field, I remembered that it was almost time for the World Series, and that meant nights on the couch with Dad, microwave popcorn, the glow of the TV painting the room in sudden blue light during every commercial break. That was the anchor, the thing that pulled all the years together—coming home in October, finding the house just warm enough inside, hearing the game on before I even got through the door.

I tried to hold onto that, to the feeling of coming home at the exact right moment, but the years wobbled in my head and I couldn’t quite pin down which one I was in. Was I the kid, sprinting the last stretch because the sun was already down and I was supposed to be home before dark, or was I the grown-up, walking slow on purpose, dragging my feet through the leaf piles because I didn’t have anywhere else to be? Maybe both. Maybe neither. I kept walking, kept breathing in the gold and red of the trees, kept waiting for the sidewalk to tell me where I belonged.

It was a strange kind of nostalgia, equal parts sweet and bitter, as if the very air was trying to remind me that every good thing has an expiration date. Each step I took on the sidewalk, I could feel the weight of every other step layered underneath it, a geology of footsteps that belonged to every version of myself that had ever walked this block—five years old, clutching my mother’s hand and skipping to match her long strides; ten and reckless, jumping the cracks with knees already stinging from yesterday’s crash; fifteen, slouching and scowling and pretending not to care that no one would walk beside me anymore. The sidewalk remembered all of it, and sometimes I thought the cracks were just the way it kept track of the years, a kind of secret calendar written in concrete and neglect.

The air that day was thick with reminders, each one as sharp as the chill on my bare arms. The sound of my sneakers scuffing over the leaves brought back the hollow percussion of a baseball in a mitt, the late-afternoon pop of a distant bat, and the echoing calls of kids who never seemed to get tired. At first I tried to walk fast, to outrun the feeling that I was somehow falling behind, but the faster I went, the more the memories stacked up—here was the house where I’d broken a window with a foul ball, and the scuffed spot on the curb where I’d first kissed someone whose name I can’t remember now. There was the mailbox that caught my backpack every Tuesday without fail, the metal bent from years of dumb accidents. None of it had changed, and all of it had.

But there was something new, too—a quality to the light I swear wasn’t there when I was a kid, the sunlight slanting sideways across the porches and lawns, so gold it looked too rich to be real. Maybe it was just the way my eyes worked now, or maybe the world really did get more beautiful the closer it got to ending. I noticed things I never used to: the way the leaves not only burned orange and red, but also curled in on themselves as they dried, little fists closing around the season’s last secrets. The way the air tasted sharper at dusk, like breathing in a promise that could only be kept if you stayed quiet and listened. The ache in my knees, subtle at first, then growing louder with every block, a reminder that the body keeps its own record, independent of the mind’s nostalgia.

I found myself counting breaths, counting steps, measuring the distance between the past and the present with whatever tools I had left. I wondered how many more times I’d get to walk this exact stretch before something changed so much that it wasn’t mine anymore. Would I even notice when the neighborhood shifted for good, when the houses and trees and people gave way to something else? Or would the sidewalk just keep holding onto my footprints, waiting for the day I came back and tried to fit myself into the outline I’d left behind?

The intersection was coming up, the one where the sidewalk forked in two directions. Every time I reached this spot, it felt like a decision was being made, even if it was just muscle memory or the pull of routine. One way led straight to my house, warm and yellow-lit and waiting; the other looped around the playground and took the long way home, past the field where the neighborhood kids still sometimes played until it was too dark to see. In my head, the fork was never just about getting home—it was about which self I wanted to be when I got there. The responsible one, the one who finished homework and set the table and answered questions with a yes or no? Or the ghost of the kid who used to rule the playground, who could throw a fastball and climb the monkey bars two at a time and never had to think about the next day, because every day was already full?

The leaves blew up against my ankles, little tornadoes of color that made the world feel in motion even when I stopped moving. Somewhere a lawnmower coughed to life, and the smell of cut grass mixed with the dry, smoky sweetness of burning leaves from down the block. I closed my eyes for a second, and in that dark, I could see October layered on top of every other October I’d ever lived, a stack of years so high it made me dizzy. I remembered the last time I’d watched the World Series with Dad, how he explained the rules in a way that made the game sound like a secret language, how he never yelled at the screen even when the home team blew a lead. I remembered the way the living room always felt different at night, somehow bigger and smaller at the same time, every corner lit up by the TV and every blanket still warm from whoever had been there last. I remembered the terror of being late, of knowing the streetlights were already on and that every house I passed was a witness to my failure to get home on time.

It was like the world was daring me to pick a lane, to decide who I was going to be from now on. But the truth was, I didn’t want to pick. I wanted to stay in the overlap, the blurry part where old and new selves could look at each other and nod in recognition. The sidewalk didn’t care which version of me showed up; it just kept going, steady and indifferent, collecting leaves and shoeprints and the slow accumulation of time.

I hesitated at the fork, suddenly aware of how quiet the neighborhood had become. The sun was almost gone, just a smear of gold behind the roofs, and the cold was starting to bite in a way that promised real winter wasn’t far off. In that moment, I felt the familiar ache of wanting everything and nothing to change at once. I wanted to be the kid who sprinted home, the grown-up who walked slow, the version of myself who would someday bring their own kid here and watch them try to jump every crack without missing a single one. I wanted to remember everything, and I wanted to forget just enough to make the present feel new.

I almost laughed at how dramatic it all felt, like the climax of a book I didn’t remember starting. But maybe that was the point—maybe every day was supposed to feel like a conclusion and a beginning, a chance to look at the same old world with eyes that had seen just enough to know how much could still change. I glanced down the block at the row of houses, each one with its own constellation of porch lights flickering on, and felt a weird gratitude for the sameness of it all. It was like the universe had decided that, just for tonight, everything could stay exactly as it was, no surprises, no disasters, just the slow turning of the seasons and the unremarkable beauty of a street I’d never bothered to name.

I kept walking, letting the sidewalk decide for me, content for once to follow the line instead of breaking from it. The sky had darkened just a little, and the first stars were starting to show, and I realized that no matter how confused I felt, I was exactly where I was supposed to be: on the sidewalk, in October, surrounded by all the colors I could never name, heading home.

For a second it feels like the year could go either way, like I could choose which one to live in, or maybe even both at once.

Searching for the great Zuby

by E. Micheal Bablin

We swept into the party in a gust of half-melted snow and enthusiasm, the air still thick with the rumors we’d trailed behind us—dumb, persistent, alive. Even before I’d kicked the slush from my boots, a stranger in a frightened yellow sweater leaned across the jammed foyer and informed us, “Zuby just left.” Not “hello,” not “can I take your coat,” but the news, hot and fresh, that we’d missed the sole reason anyone came to these events in the first place. This was the necessary disappointment, the script everyone rehearsed, and as the words landed they left a vacuum in my chest—a hollow, elastic snap like when you pull your hands apart after they’ve been glued with honey.

I stood uncertain in the vestibule, the last notes of someone’s laughter drifting around the corner and up the stairwell, the echo of a joke that had ended just before we arrived. There is a very particular aftertaste to having missed someone: it’s not absence, but presence gone molecular, something spirited into the air and taken up by every nostril. I could feel Zuby’s residue in the heat of the doorknobs, in the way each conversation muted itself as we passed, as if the room itself was a lung that had just exhaled him. Lightbulbs seemed to glow with a more golden, forgiving light in the wake of his departure. Coat sleeves brushed my own as guests shifted and repositioned, seeking a new equilibrium in his absence; I was certain that if I turned fast enough, some afterimage would flicker at the edge of vision, a blur of corduroy or the shaking tail of a sentence unfinished.

My companion (I think her name was Jorie, or possibly Jill; she preferred to be called neither) made a disparaging moue and shrugged her shoulders so far up they nearly met her earlobes. “Classic,” she muttered. “He knows exactly when to leave, doesn’t he?” I nodded, but the truth was less simple. Zuby didn’t just slip away—he became every room’s anticipated absence, the black hole around which every anecdote bent. I could hear him even now, in the story being retold by the credenza, a curling, self-regenerating narrative featuring Zuby as both protagonist and punchline. To miss Zuby was to inhabit a specific loneliness: one tinged with the hope that you might still catch him on the sidewalk, or at the very least, find a memory of him clinging to the banister or the rim of a wine glass.

We spilled further in, past the crowd of grad students and their urgent, peacock displays of cleverness, through steamy archways and into the heart of the kitchen, which was always the heart of any house worth the trouble of visiting. The counters were already stripped of their better offerings; only a single wedge of brie, sweating beneath harsh light, and a heap of bruised apples remained. Someone had lined up shot glasses full of something viscous and green, and a trio of philosophy undergrads hovered, performing the elaborate courtship rituals of their kind—lofty pronouncements, heavy laughter, strategic foot placement. Zuby was a constant reference point: “as Zuby would say,” “like that time with Zuby at the Solstice thing,” “the way Zuby just, you know, is.” It was as if the party had been engineered precisely to amplify his myth, a social echo chamber where his absence was more articulate than any presence.

I circled the rooms like a moth, certain that I’d find him if only I looked with sufficient cleverness or persistence. In the den, a woman in a cranberry velvet dress caught my sleeve and asked if I’d seen Zuby’s newest trick—the thing with the carrot and the lighter fluid—because “it’s the only time anyone really believed in magic since third grade.” She let me go only after extracting a promise that I’d report any sightings. On the back porch, a man with the hairless, unblinking look of late-stage academia offered me a cigarette and told me, sotto voce, that Zuby was really just “a symptom of the times,” proof that our generation would never recover from a deficit of authentic charisma. I smoked the cigarette to the filter just to keep him from asking my opinion.

Above all, I was haunted by the certainty that Zuby was not truly gone, only lurking in a probability cloud, waiting for me to look away so he could collapse back into certainty. I remembered every previous encounter: the time I lost him at the mall, only to discover him in a mall I’d never heard of, three hours away; the time he left a wedding in the middle of a slow dance, only to appear in the wedding photos, arm-in-arm with the bride’s great aunt; the time he showed up at my own birthday party, uninvited, and vanished again before the cake was even cut, leaving behind a signed playing card and a single, perfect origami swan. Zuby was always two steps ahead, which meant I could never catch him, but I could try, and for reasons I could never articulate, I always did.

I kept moving, because motion was the only way to stay in the gravitational field Zuby left behind. As I pushed through the crush in the living room, a volley of laughter shattered the conversation and everyone’s head swiveled toward the staircase. For a nanosecond, I felt a seismic shift—was it possible, had he returned? But no, it was only the host, flushed and panting, holding a tray of mismatched shot glasses and telling everyone that the real party would be on the roof. My disappointment was so palpable that Jorie/Jill called me out on it in front of half a dozen people.

“You know he’s not actually better than anyone else,” she said, and the words rang out with that peculiar clarity that only comes from mild intoxication and private disappointment. I didn’t answer, because the question wasn’t whether Zuby was better; it was whether I would ever be satisfied with merely being present when Zuby was not. I drifted through the rooms, gathering stories and fragments, cramming them into my pockets like so many party favors: the legend of the time Zuby ate an entire lemon, rind and all; the rumor that he once convinced a dean to cancel finals for an entire department; the whispered assertion that he’d been seen, recently, at the train station with a suitcase full of unmarked envelopes, headed somewhere no one could pronounce. I collected them all, not only for myself, but for the future moment when I’d encounter Zuby again, and he would expect me to be up to speed.

The night, as all such gatherings are fated to do, began dismantling itself with a sort of cunning inertia—a slow-motion collapse masked by the crescendo of stereo, the clatter of empties, and the mounting warmth of bodies. There’s always a moment, never marked but always known, when the party’s spirit snaps from exquisitely possible to irretrievably gone, and I could feel it happening even as I made my slow, thwarted orbits of the house. The kitchen, once a warren of tactical flirtation and wine-glass semaphore, had thinned to a few diehards pecking at the remains of the cheese plate, scraping the wax rind for dregs of flavor. The living room, which had seemed so vast and luminous when I first entered, now bristled with conversational knots—tight, insular clusters of laughter that closed ranks whenever I approached. Even the staircase, which had earlier functioned as a kind of social launchpad, now bore a single, desultory couple huddled together and discussing, in voices barely audible, whether to call a cab or push their luck for another hour.

I moved through these spaces with a sense of mounting unreality, half in the moment and half remote, as if watching my own life from a mezzanine. With every lap around the house, my certainty that Zuby might still be lurking somewhere—some hidden pantry, some shadowy guest bathroom—grew at once more desperate and more absurd. I began to notice the other repeaters, the pilgrims on their own private circuits: the guy in the baseball tee who compulsively checked his phone in each room, the woman who kept losing and then finding her purse, the philosophy undergrads orbiting the liquor table in search of a new audience for the same, slowly mutating anecdotes. In their movements I saw a kind of kinship, a silent acknowledgment that we were all here not for the party itself, but for the possibility that something—or someone—might yet happen.

As the hour grew later, the boundaries between rooms and between strangers eroded, and the house became a single, undulating organism—louder, sweatier, more prone to spontaneous eruptions of song or dance or sudden, inexplicable weeping. I found myself wedged into a hallway alcove with three acquaintances whose names I could not retrieve, all of us shouting to be heard over a Stevie Nicks song that had been put on ironic repeat. One of them, a guy with a beard sculpted so precisely it felt like a dare, confessed to having once taken a road trip with Zuby and “some girl who only ate beige foods.” This led to a round-robin of Zuby stories, each one more improbable than the last: the time he’d convinced an entire pub to sing “Happy Birthday” to a goldfish; the night he’d gotten locked in a botanical garden and spent the entire evening naming every plant after an NBA player; the semester he’d infiltrated a sorority under an assumed name, lasting nearly two months before exposure. For a while I was content to listen, letting each new tale layer itself onto my own mental collage of the man, but eventually I found myself staring at the baseboard, counting the carpet tacks, my attention fraying at the edges.

I slipped away, quietly, and drifted toward the back of the house, following the faint pull of cool air and the promise of temporary solitude. The sliding glass door led onto a narrow deck, where a handful of smokers shivered in their coats and watched the streetlights halo the falling snow. Here, conversation took on a different timbre—softer, less performative—and I found myself unexpectedly confiding in a woman with a cigarette perched at a comical angle from her lips. She asked if I was “one of Zuby’s people,” and I hesitated before answering, unsure if the category was meant as praise or mockery. When I finally nodded, she offered a knowing, almost sympathetic smile, as if to say: You’re not the first, and you won’t be the last.

We talked for a while about nothing—weather, the relative merits of local pizza places, the enduring mystery of who actually owned the house—before the conversation drifted back, inevitably, to him. She told me that Zuby had called her once in the middle of the night, from a payphone at the edge of a county fair, just to read her the entire text of a warning label he’d found on a ride called the Zipper. “He said it would be important for me to remember it one day,” she laughed, taking a drag. “I still have no idea why.” There was no bitterness in her tone, only a kind of bemusement, as if she’d long ago come to terms with the fact that Zuby’s logic was a closed system, self-consistent and utterly impervious to outside influence.

I left the deck and wandered back inside, where the party had reached its final, inevitable stage: the scattered survivors, the makeshift beds assembled from couch cushions and throw blankets, the host moving from room to room with the dazed affect of a parent accounting for children after a storm. There was a sense of aftermath, of stories already congealing into legend, and I felt a loneliness so acute it bordered on the sublime. I circled the house one last time, testing every door, peering into closets and behind curtains, half-hoping for an apparition, a last-minute reversal, a Zuby-shaped shadow thrown against the wall by the glow of the refrigerator.

Instead I found myself alone in the mudroom, staring at the heap of winter boots and coats that had multiplied during the course of the evening. I sat on the bench and listened to the muffled echoes of laughter from the other rooms, their voices at once so close and so impossibly distant. It struck me then that Zuby’s absence was not a single event, but a condition of the world—a kind of weather, always moving ahead of you, always receding even as you pursued it. I felt the urge to call him, to leave a voicemail or a text, but I knew better. The game was not to reach him, but to keep reaching, to stay in motion even as the coordinates shifted and the target dissolved.

Sometime after two, I found Jorie/Jill slumped in the armchair, her posture gone loose and provisional. She roused herself enough to smirk at me and say, “You’re still looking for him, aren’t you?” I didn’t deny it. Instead, I asked her if she thought anyone would really remember this night, or if it would just blur into the general wash of parties and semesters and years. She thought about it, then said, “Every story needs a Zuby, even if he’s not around to hear it.” I liked the sound of that, even if I wasn’t sure I believed it.

As the party dwindled and the house emptied, I began to help with the cleanup—tossing bottles, stacking plates, wiping the sticky residue from the counters. It was a small act of faith, a way of insisting that the night had mattered, that the evidence of our presence should linger at least until morning. For a while I worked in silence, then with the host, who was grateful but too tired to say much beyond thank you and good night.

Eventually, with the house returned to a semblance of order, I stepped outside into the cold, the snow now falling in thick, leisurely flakes. The street was empty, the windows of the neighboring houses dark. I stood for a long time on the porch, letting the night air bleach the noise from my head, and thought about all the places Zuby could be—some after-party, some diner, some train already out of town. Or maybe, just maybe, he was nowhere at all, content to exist in the stories we told about him.

But I kept moving, scanning every face, every doorway, every possibility, waiting for the moment when the great Zuby would materialize again—if not in this lifetime, then in whatever lifetime awaited the people who never learned to stop hoping.

Christmas Kitten,

With a little red hat and a jingle bell collar,

He hopped on the sleigh, ready to holler

For every stray cat, wandering in the cold,

He brings them warmth, love and stories untold.

Through snow and wind, he bravely goes,

To bring joy and hope, to all those in woes.

For Christmas is not just about presents and toys,

But spreading kindness, to all girls and boys.

So let us remember, this little Christmas Kitten,

And all the love, that he has written

On the hearts of many, with his fluffy paws,

Bringing peace and love, without any flaws.

Christmas Kitten, will always be there,

Spreading love and joy, in the chilly air.

For we are all God’s creatures, big or small,

And Christmas is a reminder, to love one and all.

They had sworn an oath, the protectors, an alliance forged not from trust but necessity—to guard the princess, who was now Empress of the Warrasua. She would travel by proxy and by fate alone; her future settled by signatures, her name now Argonne. She was only fourteen, Princess of the First League, selected for a distant Emperor as the last desperate offering to peace. “The Confederation of the Three Leagues” was once vibrant, full of energy and rivalries and life, but the great war broke it into fragments. Millennia of fighting meant a century of devastation. Millions dead; the plague that arrived after the slaughter gnawed on the skeleton of hope, left in the eleven empires. All that remained was unity—but unity in name only, pieced together with treaties and arranged marriages and brittle words, nothing like what came before.

The journey itself was ritual as much as passage—a procession across darkening waters, carrying with them the future. Argonne’s retinue: Arcturus, first among her companions, and a solemn guard numbering twenty-seven. Their purpose, explicit and sacred, was to accompany the royal girl to her distant, unknown sovereign and the awaiting court.

On deck, days and nights passed in salt-silvered cycles. What gave Argonne comfort, or at least distraction, was her gathering of stories. She collected fables, seemingly naive and harmless, plucked from the memories of her shattered league like small, pale feathers from some extinct bird. Yet with each new tale, she began to sense the depth beneath the surface—a sediment of secrets, causeways of memory, each myth carrying more torque than anyone could have believed. The innocent-seeming narrative, once deciphered, would change everything.

The first and longest stretch of the journey was always the sea, and so it was now: Argonne and her retinue adrift on tide and treaty, bearing the collective future of their people toward the unknown. The ocean, in this latitude, was not temperate blue but a roiling slate, each passing hour bringing a heavier ceiling of cloud to press them downward, until the very act of breathing seemed an affront to the weight of the world. The water carried not only their ironclad vessel, but also the ache of all who had sailed before—armadas and refugees, the grand flotillas of empire, and the hollow-eyed survivors of the last Confederation war, exiled to the margins of memory. The brine was inescapable; it clung to skin, marinated every cloth and hair, and left tongues swollen with an unquenchable thirst. There was a myth, Arcturus told her, that the sea was simply the mouth of some ancient and patient beast, and all rivers were the routes it used to taste the world. To Argonne, the sound of the waves lapping the hull became the low, reverential chant of that monster—waiting, always, for the next mouthful.

The ship was a relic, its bulk imported from a dynasty so ancient its makers were a rumor. Even so, the vessel had been retrofitted for this singular voyage: every hold and cabin sealed, every deck reinforced, every window replaced with shatterproof glass. The crew, like the ship itself, seemed assembled from mismatched centuries. Old men who still believed in ghosts and omens. Young women who slipped between languages with the agility of cats. Hungry orphans, indentured for the promise of a meal at journey’s end. The captain, a woman called Mraz, wore a coat braided with medals from every empire, but she trusted only the compass she kept chained to her throat. This was the company that ferried the future Empress of Warrasua, each member sworn to secrecy and survival, their loyalty as brittle as the salt caking their boots.

But the ship’s true cargo, and the reason for all this ritual and vigilance, was Argonne herself. She spent most days in her cabin, confined not by decree but by the gravity of her own thoughts. The space was sparse: a cot, a desk bolted to the floor, a single trunk containing letters of state and the ceremonial garb she would wear upon her arrival. Arcturus alone was permitted to join her for meals, though most days the two sat in pointed silence, the air thick with unspoken fear. At night, after the lamps were doused and the decks patrolled by the silent honor guard, Argonne would rise and pace the length of her quarters, reciting the stories she had gathered, her voice a hushed counterpoint to the restless sea.

She had begun this habit as a child, back when stories were simply stories and not the currency of survival. Her mother, a Queen of the First League, taught her that every myth was an encrypted map—each fable a vector in the greater geometry of power. Now, with every recitation, Argonne sifted for patterns, for molecules of meaning that might be recombined into the formula for her own fate. She was not naive: she knew that history was a ledger, and that her name, newly minted, was already being balanced against the debts of a thousand ancestors.

On the thirteenth day, the lookout announced the first sighting of Skyborn, the port city that marked the edge of the Classbe Empire. At first it was only a rumor on the horizon, a distortion in the air, then a finger of smoke, and finally the silhouette of towers like ribs prying open the sky. The anticipation on deck was palpable, the guards assembling in their finest livery, their faces composed yet tight. Arcturus brought her news of the city’s approach, and for the first time in weeks, Argonne found herself drawing a full breath.

Yet with every mile nearer to Skyborn, the air grew heavier. Stories abounded of the city’s cruelty: how the Classbe lords preserved their own dead in crystal and displayed them as warnings; how no foreigner had ever left its gates unchanged, and most never left at all. The city’s walls were rumored to be laced with the bones of conquered peoples, and its libraries were said to contain not books but the preserved tongues of traitors, catalogued by dialect and infraction. Even the sea recoiled as they drew close, the surf churning with a violence that seemed personal.

The guards conferred in whispers, their formation shifting to cover every approach, as if they expected an assault from the very air. Mraz, the captain, summoned Argonne to the bridge for the formal briefing. There, she explained the approach protocol: they would sail under a flag of truce, fire no cannon, and transmit their cargo manifest to the city’s harbormaster in perfect transparency. Any deviation would trigger a response from the skyward batteries, which could sink a fleet in one volley. Argonne listened, nodding at every clause, her mind already mapping the routes of escape, the tones of deference she might employ, the way each word would weigh against the scales of suspicion.

When the city finally enveloped them, the effect was total. The sound of the sea was replaced by the clangor of iron bells, the caw of engineered carrion birds, the ceaseless grind of gears and pulleys that moved the city’s great bridges. Porters swarmed the docks, faces masked in the livery of their syndicates. The docking itself was an ordeal: first the ship was boarded by inspectors in mirrored helmets, who sniffed every crate and scanned every document, then the passengers were led single-file onto the wharf, each one branded with an invisible mark that would track them through the city’s labyrinthine streets.

Argonne walked at the center of her procession, every eye upon her. She wore the ceremonial white of the First League, the fabric so fine it seemed spun from cloud. At her side, Arcturus looked less like a companion and more like a sentinel, his hand never far from the hilt of his blade. The walk from the dock to the Embassy was less than a mile, but it took hours, each intersection guarded by checkpoints and crowds of onlookers. Some jeered, others stared with blank, predatory curiosity. Argonne kept her gaze ahead, replaying the fables in her mind like a shield.

The embassy was a fortress of glass and stone, staffed by a skeleton crew of loyalists from the old Confederation. Here, at last, the retinue could rest. The guards were billeted in a barracks carved into the embassy’s basement, and Arcturus disappeared to confer with the city’s intelligence contacts. Argonne was escorted to the diplomatic suite—a room that smelled of wax and old paper, its windows shuttered tight against the possibility of listening devices. The only decoration was a mural depicting the founding of Skyborn: a thousand faceless figures kneeling before a single, red-caped ruler.

Alone for the first time since their arrival, Argonne allowed herself a moment to collapse. She lay back on the stiff embassy bed and stared at the mural, tracing the arc of each kneeling supplicant with her eyes. Somewhere in the city, the Emperor awaited her, ready to claim the prize that was her life and name. She wondered if he knew the stories she carried, if any of them would matter, or if she was merely another offering to the maw of empire.

Yet even here, marooned on the far side of history, she felt the old compulsion: to gather, to catalogue, to retell. She rose from the bed, found a scrap of paper and a pen, and began to write the story of her own arrival—not as a victim or a pawn, but as the last, defiant archivist of the First League. It would be a small thing, likely destroyed or forgotten, but she would leave it nonetheless, a fable embedded in the bone of this place.

“You can only go forward by knowing where you came from.” The words echoed, ballast against the ocean’s rolling uncertainty. Argonne drew from the past at every turn, gathering fables from the first league and committing them to mind with careful diligence. With Arcturus and the other companions, the fables multiplied. In the gentle hush of her quarters, she whispered them aloud, fingers tracing sigils in the air as if each story could steer her ship or her heart toward safety.

Stories had always clung to her, tenacious as the salt in the seams of her cloak and persistent as the tides that battered the hull. They did not only follow Argonne, they defined her. Every fable—a fragment of myth or memory, gleaned from the old halls or whispered in sickrooms back home, now bundled tightly for the journey—not only promised survival but created its own strange gravity, pulling at her with a weight that could not be ignored. The Confederation, gaunt with war and parched by plague, fastened its last longing for peace on the slim promise of a child’s untested oath, and upon those thin-walled vessels of understanding that legend alone could shape. Argonne herself, just fourteen, crossed the Great Sea with twenty-seven companions. Her only inheritance: stories, hoarded and sealed against cold or doubt, her future interleaved entirely with scrapings from the past, myth, and the brittle hope that some hidden lesson within might prevent disaster.

Initially, the Princess did not speak. Nothing at all. Their party departed in silence from Ammerall’s citadel, leaving behind the unmoving gray of the stone towers, the hush of emptied corridors, the cold that filled a place when its voices faded out for good. She retreated to her cabin, almost vanishing inside herself, a breathless hush more than a presence. Everything about her—the stillness, the way she folded her limbs as if to vanish into air, the squared jaw when spoken to but never answering—made it clear she was not ready to let go. Not her homeland, not the friends knotted around her childhood, not the echo of steps she once matched stride for stride along castle galleries. Only duty, fraying but unbroken, bound her to the voyage. Sometimes she dreamed, but only in fragments: the freedom to choose, not simply the unyielding cloak of responsibility, so heavy it smothered every other wish. That was gone now, replaced by the endless ship’s beat and the relentless ocean, carrying her toward a future determined not by her but for her. Her fate: to marry a stranger, serve a cause she could not decipher, and deliver herself to a people condemned as savage, feared as cannibals. She was told it would bring peace, though the logic of that sacrifice eluded her. Resolute and isolated, the Princess endured, and her stories endured with her, as if between them they might anchor her to a version of herself she could still claim.

By E Micheal Bablin c2025

There are those people who write novels in this world to become famous and make money, bestseller-list types who stalk the market and trend like wolves, noses twitching for the next fix of relevance, casting their prose as bait for film options. Their faces, you see, float on the backs of dust jackets in big-box bookstores, grinning through a veneer of mass-appeal, all flashbulb and advance checks. Some of them probably never even cared if the words themselves meant anything, so long as the words accumulated, like landfill, under their name. Even when the author photo is blurred or cropped, the impulse beams through: they want to be known, to be quoted at dinner parties, to have their words dropped like incantations by late-night hosts and columnists. They chase the reader’s gaze as if it might transmute them into something more than a clever monkey in a blazer with a contract. If you ever talk to one at a conference—say, over the ruinous chardonnay of a hotel bar—listen for their hunger: it is half shark, half showman. They speak of “platform,” not legacy; of “audience,” not language. Their epics become franchises, their epistolary novels thinly-disguised bid sheets. Fame, money, or at least a memorial plaque on the wall of a chain coffee shop in a suburb.

There are those people who write novels in the world because they’re notorious, or who seem to take a weird, unwholesome pleasure in the propagation of violence and mayhem. They’re not the same as the bestseller wolves, exactly—instead of hunting the herd, they want to scatter it, incite a stampede, let the bodies pile up and call it literature. They sharpen their sentences on the bones of other people’s suffering; they build entire careers out of spilling blood on the page, delighting in the fallout and public outrage. They are the connoisseurs of infamy, the engineers of controversy—writing not so much to seduce the reader as to punch them in the face, leave a bruise, maybe even a permanent scar. Their works become the forbidden objects in high school lockers and under dorm-room mattresses, banned from libraries but circulating like a viral disease in the dark. you know them by the way they cultivate enemies, by the way their very names can silence a room, by the way they seem to relish the public burnings and the hate mail. They want to be infamous, and if it takes a little literary arson to get there—burning bridges, torching reputations, immolating the last remaining taboos of the century—they’ll light the match, every time. There is a theory that these writers are acting out a larger social necrosis, the death wish of an empire in its decline, but I think it’s something simpler and sadder. They like to make trouble, and this is the only way left that’s legal.

Then there’s the third way. The third way is made up of people who never had any right to write a novel at all, at least according to the world. Not the trust fund Ivy kids or the wounded prodigies, but the ones who came to language late, sometimes backwards, sometimes sideways, sometimes as a byproduct of jobs, or illness, or the accidental slant of immigrant voices at the dinner table. They were born into the permanent backdraft of the American machine, churning out their years in check-out aisles, food courts, car washes, nursing homes, and high school kitchens—learning the shape of words only as a function of survival, not as a ladder to some cathedral of taste. These writers didn’t start with books in the house, or if there were books, they came second-hand, water-damaged, or found in a dumpster beside the old TV and the remnants of last night’s Hamburg and Peas. They wrote because no one else was ever going to write about them, or for them. They wrote because the stories in their heads were the only inheritance they’d ever be allowed to keep.

You’d know them, if you met one, by the stains on their hands or the way their knuckles tell the history of shit jobs and self-repair. Their sentences might have strange gaps, like teeth knocked out in a bar fight, and their grammar might lurch or limp, but every line is a compulsion, a work-around for the way the world never gave them a straight shot. Some of their stories are patched together from borrowed library time, written in spiral notebooks that crook and …., or typed in the flicker between the second and third shift at a job that’s killing them. Many writers exist in a hidden canon, unpublished and uninterested in publishing, doubting anyone would care. Who would listen? The answer: almost no one, until the day someone does, and then it gets out that the best stories come from the people with the least reason to tell them. If you read these stories, you’d find yourself in the company of voices that have never been on a panel or a syllabus, voices that have gone hoarse from shouting over the TV or the factory floor, voices that know what it’s like to get a rejection letter and use it to line a birdcage, or light a fire, because that’s what rejection is good for—fuel or bedding.

They are not much for manifestos or trends, these working class scribblers. If you asked what they wanted, they might say something like: “I just want to tell it like it was.” Or maybe: “I want to make a story that sounds like how people really talk, not how they think they should talk on the radio.” They live in places where literature is mostly a rumor, and “writer” is maybe the word for the guy who sets up the menu boards at the pizza place. Their ambitions are not for accolades, but for accuracy: to get the feeling right, the moment right, the punchline right, the way the world can be cruel and hilarious in the same breath. Their audience might be no one at all, or maybe just the one person they secretly love, or hate, or need to impress because that person is their entire universe and the only review that matters. They don’t have MFA workshops, but if you listen, the break room or the bus stop or the back of a Denny’s at three a.m. is its own kind of creative writing seminar, and you can hear the edits happening in real time.

Now and then, one of these writers gets loose in the world and the world doesn’t know what to do except make it a novelty, an anomaly, a “voice from the margins.” They get described in profiles with words like “gritty” or “authentic” or “raw,” as if the work itself is a slab of meat and not the fragile labor of a person who would have gladly taken a better life over the chance to write about a miserable one. But here’s the trick: their stories will outlive all the others, because they contain something the market can’t synthesize, and the controversy-mongers can’t fake—something like truth, or pain, or a sense of humor about the whole goddamn mess. It’s the third way, the unglamorous path, the slow leak of language from the bottom of the world. This story is written by one such person.

E Micheal Bablin

by E Micheal Bablin

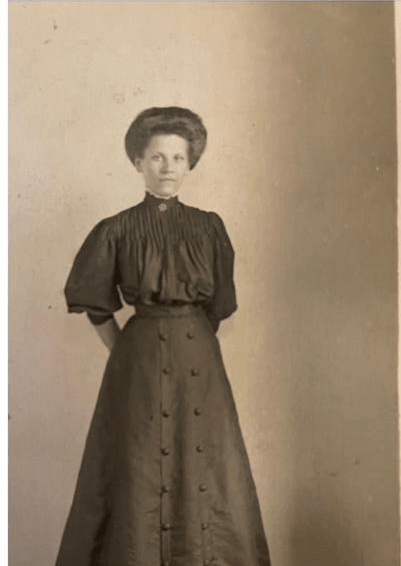

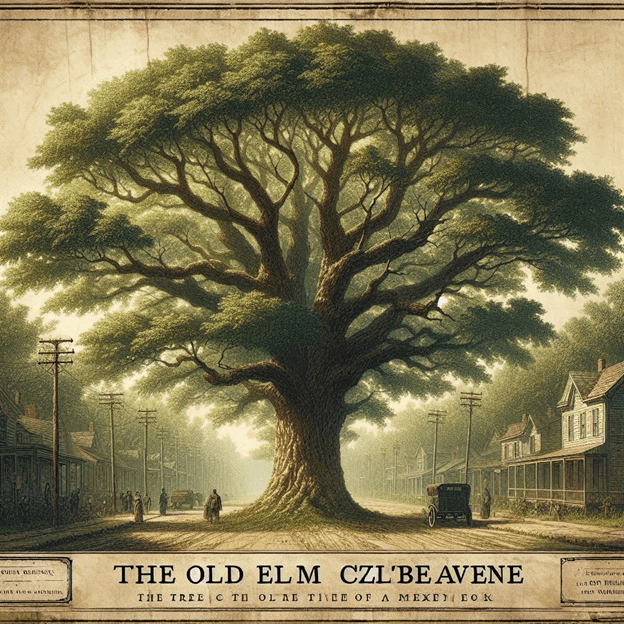

In 2002, I was cleaning out my parents’ house on Clizbe Ave, Amsterdam, NY .

In the attic, I found a collection of antique stereoscope cards. I saved the collection from the dumpster and took it home. Among the cards was a photograph. It is a photo of a woman, dressed in a per-World War I fashion.

Searching for her identity led me to the story of the modern cardboard box, and its conceptual design, which begins in Amsterdam, New York. I discovered that this woman (Jessie Warner) is a daughter of John Warner.

John Warner was the President of the American Box Machine Company (ABMC) in Amsterdam. This public Company was incorporated in 1885. John Warner was President, Horace Inman was manager, Arthur De Forest was Treasurer, and Bernard Finlayson was Secretary. In 1885, the cardboard box was cutting-edge technology. Everything before then had to be shipped by the barrel, crate, or in a bottle. The invention of the cardboard box led to a significant decline in shipping costs, and the person who held the patent on this machine stood to make a fortune.

John Warner, who arrived from England in 1856 and settled in Amsterdam in 1860, resided on Pearl Street. He married a Scottish woman, Jannette Mitchell. They made an acquaintance with a close neighbor, Arthur De Forest. Warner and DeForest had their own knitting mill. Warner, from England with a Scottish wife, made their acquaintance with another Scotsman, Robert Gair, who held the patent rights for the box machine.

Of course, there’s a world of difference between conceptual engineering and practical engineering. The practical engineer was Horus Inman. Horus was a self-made man; his parents died young, and he was raised by relatives in Hagaman. He taught himself engineering.

What Warner and Inman needed was a nice, quiet place to build their prototype. The road from Hagaman to Amsterdam took Inman down by the old Clizbe farm in sparsely populated Rock Town, past the old flower mill. Inman and Warner built their prototype in the old flower mill in Rock City, now located at 2 Hewitt Street, Rockton, Y. The prototype of the first modern cardboard-making machine in America was made in this place. We know it today as the Creekside restaurant and brewpub.